J.D. Salinger wrote himself into American letters in 1951 with “The Catcher in the Rye,” an enduring best-seller about the young, rebellious Holden Caulfield that still graces high school English curricula. But despite his early success, Salinger spent the rest of his life hiding from his own celebrity.

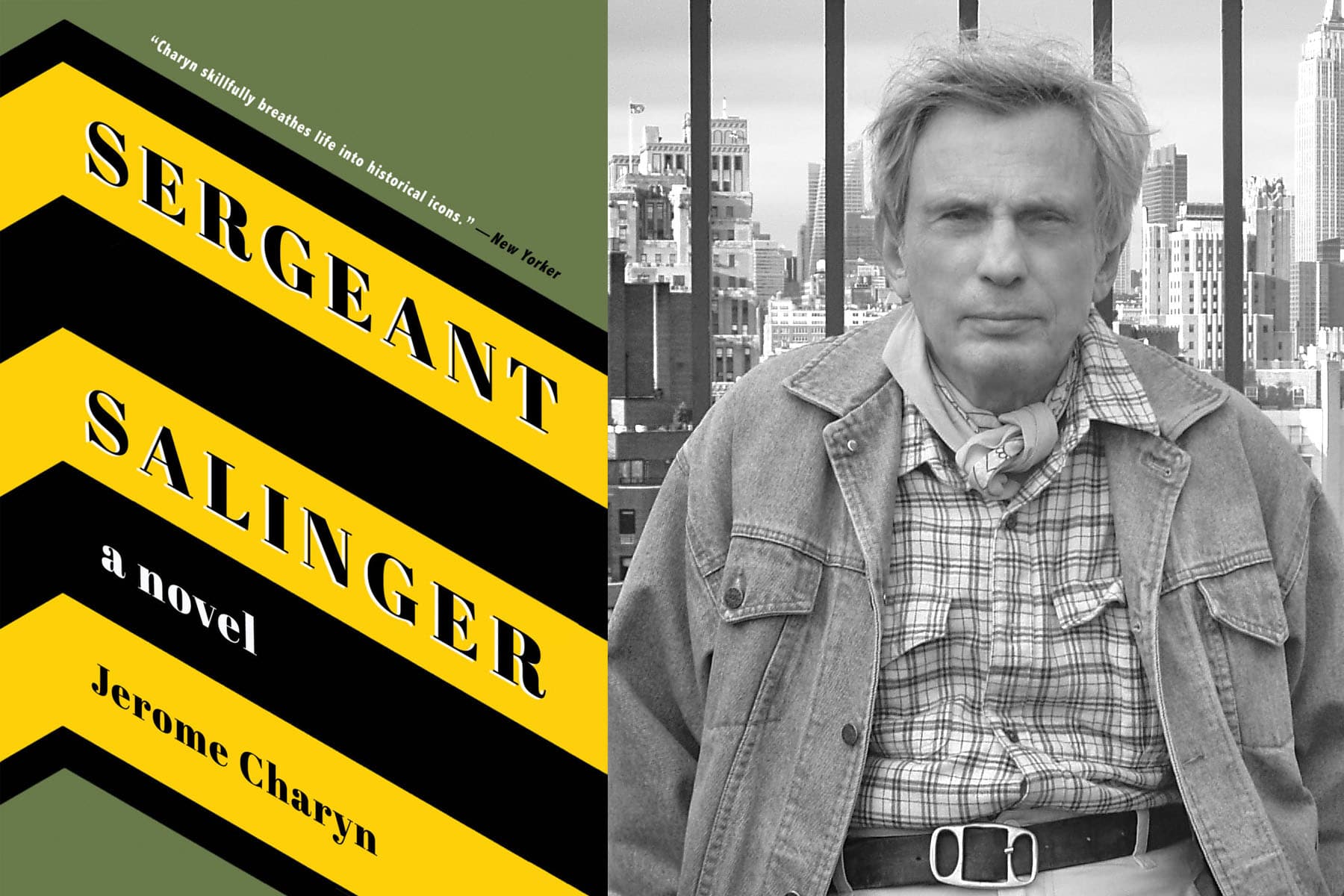

Now, Jerome Charyn, a distinguished author with more than 50 books of his own, has dared to conjure up a quasi-biographical novel about Salinger in “Sergeant Salinger,” a tour de force that allows readers to meet a “lanky boy…with big ears and olive skin and a Gypsy’s dark eyes” — variously known as Sonny, J.D., Jerry or “a tall Yid,” per celebrity columnist Walter Winchell — and to follow him into combat in World War II.

Charyn, as he has proven time and time again, is a master of the written word. “Sergeant Salinger” opens with the explosion of a literary star-shell at a high-powered table at the Stork Club in 1942. Walter Winchell is presiding over the table, and the “volupu-u-u-u-u-ous” Oona O’Neill, daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neill and future wife of Charlie Chaplin, is Salinger’s date. Ernest Hemingway, Salinger’s hero and role-model, comes over to say hello. Back at the Salinger family home on Park Avenue, J.D.’s mother hands him a letter that has arrived only that day — a draft notice.

Thus Salinger, “who scribbles at home like a little rabbi” but aspires to be the next Hemingway, and whose “slight heart murmur no longer matters to Uncle Sam now that the military was in disarray,” is plucked from his privileged life, draped in a sergeant’s uniform, and dropped into the Counter Intelligence Corps — “a ghost with an armband, a pistol, and a gold badge.”

Charyn tells his tale with a wink and nod to the biography of the real J.D. Salinger. The fictional Sgt. Salinger “started a novel about a prep school boy who went on the prowl and never return to school,” Charyn writes, but now, he was assigned to the intelligence unit that would accompany the frontline troops in Normandy. “Soldiers of the CIC would be the first to enter a captured French village,” he explains. “They would root out collaborators, chat with the mayor and chief of police, determine who could be relied on and who had to be shot.”

Charyn tells his tale with a wink and nod to the biography of the real J.D. Salinger.

At moments, “Sergeant Salinger” reminds the reader of “Catch-22” by Joseph Heller. When Charyn recreates the training exercise at Slapton Sounds — a real-life mock landing that ended in mass casualties from friendly fire and German boats that happened upon the exercise — Salinger’s job is to hide the evidence of the snafu.

“To certify that we were never here,” his captain explains, “You are to cover up every mark we leave behind.”

“’But there are naval guns firing right at us, sir,” Salinger replies.

“‘That’s Force U,’ the captain said. ‘And Force U doesn’t exist.’”

Sgt. Salinger turns up at other key places in the real-life history of World War II. He lands at Utah Beach in the second wave. He serves in the Battle of the Bulge, where “the Allies had to take one tree at a time.” He is assigned to the French army that was given the honor of liberating Paris. Ironically, he is ordered to arrest Ernest Hemingway for leading “a rogue’s regiment” of armed civilians into the city: “He’s shot his way to the Place Vendome and liberated the Ritz,” writes Charyn.

“It was a sort of an inconvenience for Sonny,” Charyn pauses to explain. “He couldn’t stop beside a country road and peck away at his Holden Caulfield novel on an army-issue Corona.”

Salinger participates in the discovery of a war crime when a pervasive stink leads his unit to the remains of a camp for sick slave laborers, now dying or dead. “Salinger, don’t go in there,” he is warned. “The Lord has left the lights out in Bavaria.” But Salinger “couldn’t abandon this assembly of forgotten souls — Gypsies, Serbs, Jews, and half Jews, like himself.”

But Charyn invites the reader to conclude that Salinger’s bitter experience of the war — what we would today call PTSD — was the reason why he lived such a reclusive and mysterious life. This point is made when Salinger’s mother, Miriam, tries to reach him when he lingers in Europe, where he served in the denazification program and yet bizarrely decided to marry a woman whom he had interrogated as a suspect collaborator.

“She couldn’t seem to get Sonny on the line,” Charyn writes. “Sometimes she got a captain who had no idea where Sergeant Salinger was, or if he existed at all. But he did exist. Once he even called, pretending to be a general, and said that Sergeant Salinger was on secret maneuvers and would get in touch the moment he could.”

“‘Sonny,’ Miriam screamed into the phone, ‘you’re killing me. Can’t you admit who you are?’”

Two intriguing suggestions are buried deeply in the story that Charyn tells so compellingly in “Sergeant Salinger.” One is that Salinger could have but chose not to write one of the great war novels of the twentieth century. (In a real sense, Charyn has done it for him.) The other is that Salinger’s experience of war drove him to explore only the inner lives of the characters he invented and to hide his own inner life from the generations of readers who revere him.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.